Math Reformed

Good Ways Up

Testimony

Memories of great people we had the privilege to consult in the past

Steve Zelditch was a great mathematician and talked with infectious enthusiasm about applications to science. His favorite themes were the harmonic oscillator, and the science of glass.

Eli Stein was the leader of one of the biggest harmonic analysis schools in the world, following in the footsteps of his advisor Zygmund. He liked to sit up front in the taxi to chat about politics with the driver. It was difficult to get Eli to give people advice and he would repeat that he could not take responsibility for everyone's outcomes. He was average height and complained bitterly about frat houses where they separated the guys into tall and short for competitive games. He said that he would like to believe in God, but trying to take on a total relationship with God might just end up in insanity.

Raoul Bott was a topologist who would explain a problem from the basics up to the cutting edge. He gave beautiful talks for example exhibiting an articulated lever set with loose joints and explaining how adding joints could result in rather random behavior.

Jean-Michel Bismut worked on torsion. He drank strong coffee like many French people, and his ambition was to be the master of the female administration department in order to get what he needed within his time frame. Before the Gulf war he said that the situation seemed absolutely hopeless but nevertheless he was hopeful. It was rumored a few years ago that he died, but he is thankfully still alive according to the web.

Daryl Geller was a kind person who like many people might have had issues balancing his mathematical career with his family life, in his case because he might have suffered from a drug problem in his family. He was extremely optimistic and encouraging, egalitarian and idealistic as though he had just stepped out from the flower power era. He liked to focus on building up other people's confidence to work in math.

Richard Hamilton was interested in two things, mathematics and enjoying himself. As a mathematician he had a very organized mastery of the subject of geometric differential equations and asking him a question could easily result in a perfect flawless two hour lecture. He was like a walking text book of several thousand pages. Enjoying himself seemed to mostly involve the outdoors from his convertible sports car to surfing, riding his horse, and playing polo. What separated Richard from the masses was his politics. He thought that the way to reduce car emissions was for the poor to not drive. Whilst Richard was a snob about class, he was an enthusiast when it came to women. He took an interest in teaching math to women students and talking math with women mathematicians. He also had male mathematician friends who were people who liked to talk about geometric differential equations for days at a time. He was a bit snobbish about mathematical fields and could sometimes upset people by believing their fields to be less important when it came to hiring and resources.

Fred Almgren was a leader in geometric measure theory following on from his famous advisor and master inventor of the subject Federer. He married a mathematician and ran his mathematical social life from his home. Whilst he worked in the same department as Eli Stein, and whilst their topics of interest ought to have had a large overlap, it did not seem that they capitalized on it. Eli specialized in running a big school whilst Fred focused more on developing a few students and on his small graduate class. The big example in his technical and delicate field is many connecting soap bubbles and how they form and connect. Fred was proud of the fact that he had been a military fighter pilot, and was quite interested in constraints of nature which are important when you try to fly upside down.

John Conway had a large mind with ample computational space and storage. He was keen to impress people and worked on big things like the monster group. He also had a great balancing and juggling show he would perform for his students in the US where he swung a penny around balanced on the hook of a coat hanger whilst hopping on one leg and juggling balls with the other hand.

Genevieve Knight was popular with her students. Young men often took her class on set theory and logic, which explained complex aspects of the subject in simple terms. Genevieve was herself somewhat self taught prior to attending college, and she based her course primarily around a drill of homework problems.

Maryam Mirzakhani was an Iranian mathematician who came to the US as a Ph.D. student and stayed here to work. When she was on the job market, UCSD and Stanford were both trying to hire her. Maryam was the first woman ever to receive the Fields Medal, the top prize in mathematics which is awarded every four years to the best young mathematicians who are not over 40 when it is decided, It is not surprising that several schools were interested in Maryam's fundamental work. Maryam was very serious and focused professionally, and tended to avoid general chat. Her family were Muslim which is to be expected because they are from Iran. Maryam married a European in the US, and chose to work at Stanford where he had better job prospects as well. Unfortunately Maryam died of cancer, under medical treatment at age 40. This was a tragic loss for mathematics.

Jean Bourgain arrived in the US around 1991, a new Fields Medalist originally from Belgium who was touted as the top analyst in the world. He worked at the Institute for Advanced Study where he could do largely whatever he wanted. He settled into his role, making the rounds of top mathematicians asking them whether there were any problems that they did not know how to solve because he, Jean Bourgain, wanted to score. He produced a large collection of complex solutions, and later settled down to educate a few graduate students. He worked and competed a great deal with the Caltech mathematician Tom Wolff. They were always getting an epsilon better than each other, but remained good friends. Sadly Jean Bourgain died at the age of 64, missing a lot of results he could otherwise have squared away.

Thomas Wolff was one of the mathematical giants of Caltech. He was a very technical mathematician working in technical aspects of partial differential equations. If he had to write an exposition about his work and was limited in how many pages he could take up he would write in tiny little text with reduced margin size. He loved to demonstrate the intricate detail of the analysis he was working on. Like much of the US, he had a mixed racial heritage. He was fundamentally a Californian and liked to talk math with the experts who wanted to talk about math details. His main collaborator was the Fields Medalist Jean Bourgain. They were a bit competitive but never ceased flying across the US to visit each other. Tragically Tom died in a car accident. He would make long road trips in short time spans and might have been prone to speeding. The US highway is not the autobahn. Tom was an amazing mathematician and his death was a loss for his field.

Carl Fitzgerald was not a famous mathematician like many of the names on this page. He was a nice friendly professor who taught many classes of students the important subject of ordinary differential equations. He was easy to talk with and focused on doing his job.

Normal Alexander Shenk, known as Al Shenk, was a mathematics professor at UCSD and an educational innovator who liked to bring more computer visuals into teaching calculus. This is something we now take for granted, but Al was one of the pioneers of mathematical graphics in education.

Michael Crandall was quite a showman. With his flamboyant personality, he became the department Chair at UC Santa Barbara. He once explained how to write a letter of recommendation for math students applying for places in graduate school, or junior positions. He explained that at least two thirds of the letter should be about the recommender's credentials to evaluate the candidate.

Alan Mcintosh was an Australian mathematician who was famous for solving open problems in harmonic analysis. He worked with harmonic analysts around the globe. At the end of his career he left the Australian National University in Canberra to develop another institution, although he shared his time between the two. He had a friendly personality and liked to welcome visitors to Australia and although he did not visit the US very much he was well known in California where he got his Ph. D., as well obviously as being known of worldwide as the main Mcintosh on dozens of important research papers in harmonic analysis for many years.

When he became older, Lars Hormander became less intimidating. He worked in differential equations in Sweden, and visited the US at various times. Mathematicians at MIT who were slightly junior apparently thought he was a god. He wrote some ground breaking books and papers that influenced the field for decades. Lars was often asked to referee papers and he would read the paper until he got to the first mistake at which point he would reject it and not read further. Lars did not seem to be ashamed of his reputation. He told a scary story about how he had explained a student's Ph.D. dissertation to the student, at which the student fainted with the shock that he had not really understood his problem. When the student recovered, Lars completed the explanation. Lars seemed to treat international math as a sport whereas other groups of mathematicians developed more supportive and less competitive international schools where mathematicians could socialize, brainstorm, have fun, relax, chat, get things wrong, and fix it all on closer consideration the morning after.

Graham Allan was a model of organization and politeness. He apparently had served as a pilot in the military and was not afraid of flying because in his own words he lacked the imagination. His lecture course was a work in progress and he worked on presenting it with crystal clarity so that even if students in the audience were tired and their eyes closed, it could still be understood without looking at the blackboard. The one challenge was his habit of numbering lemmas, theorems and propositions sequentially through the entire course. Students eventually learned some of these numbers off by heart so as to know which result he was referencing.

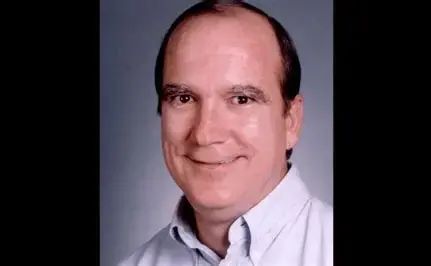

Irving Segal must once have looked just like this, but it is hard to find a picture which is recognizable as Irving in his later years, full of energy, handing out T-shirts to MIT math students to get more publicity for his unusual theory of the universe. Irving is credited with having had perhaps as many students as some of the big Russian names in mathematics. He was apparently a second advisor to dozens of students. He had an alternative theory to the big bang which hypothesized local expansion regions of matter compensated for elsewhere.

Although nobody from Good Ways Up actually talked with Israel Gelfand in person, we got to see a lecture that he gave at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton when Karen Uhlenbeck invited him to speak. Gelfand was perhaps one of the most famous names in mathematics despite working mostly in Russia. This is partly because of his famous lecture series where mathematical prodigies started studying at age 14. Russia was known to have large schools in math headed by single powerful mathematicians who made all of the decisions. By comparison, the atmosphere in mathematics in academia in the US was far more egalitarian with all kinds of democratic constraints to prevent mathematicians from dominating their colleagues. Gelfand's lecture at IAS was suitably impressive. He had a line of ex-students sitting in the front row in dark business suits, some over 40 years old. Gelfand walked around the stage and the aisle of the lecture hall pondering on philosophical observations. Then he would beckon one of the students up to the board and command them to write it down. The student would write a complicated equation involving quantities from mathematical physics which was apparently correct, but which only the well prepared members of the audience got to copy because Gelfand followed his ex students with an eraser so the beginning of each of the formulas was already gone before it was all written down.

Ray Redheffer worked as a math professor at UCLA, and was popular with students for working hard to explain the subject of differential equations. He liked to run his course so that it would have the comfortable demands of a grade school math class, where the students learned techniques by working lots of examples. That made Ray popular with the students, because they knew that the amount of work they put in would most likely lead to a proportional grade at the end. It was a practice makes perfect situation. In addition he fully engaged in the Southern California focus on health and fitness. He put up an exercise bar in his office above the doorway so that he could challenge himself to be able to do more pullups in his spare moments.

Harold Widom was a friendly mathematician who was quintessentially a West Coast USA math professional. He selected a field which had some engineering applications and focused on being an encyclopedic expert in that one field. He developed his own notation which he claimed was perfectly suited to suffer as little loss as possible during computation. As usual in analysis, every reasonable calculus computes the singular terms, but only the best ones keep track of smooth terms. If the calculus is only giving you the leading order term, then that is an interesting field for a new young Widom.

Stephen Siklos was an example of a male academic who taught and eventually became director of studies of mathematics for an all Women's college. The college is part of Cambridge University. The colleges in Cambridge University provide their students with accommodation and tutoring, whereas the university serves all of the colleges and runs the lectures and examinations. Stephen was a university lecturer which is a mark of academic distinction, as well as being a college lecturer which obliged him to spend many hours grading student homework and supervising students. Cambridge University used to be a competitive and intimidating environment for many students. It was not just that the lectures contained a lot of material and were run rather fast, and the same for the exams, but the students themselves could be competitive and in particular perhaps 40% of the students had attended all boys schools before going to Cambridge. Some people had the expectation that the best students were young male geniuses, and the women were likely not all that bright. This meant that women sometimes contented themselves with the extensive Cambridge social life and did not put all their ambitions into their subject. However, Stephen Siklos tried to keep his girls spirits up, and the way he did it was with indulgent admiration of their mathematical capabilities. He was all modesty about his own achievements, claiming that he was a rather ordinary Cambridge mathematician. He was he assured the girls, nothing special. Obviously this was largely irrelevant because he most importantly knew how to solve every problem that was ever likely to come up on the Cambridge exams in mathematical physics. The way he treated his student's budding work was however with immense respect. He would remark that their homework solutions seemed effortless, were superior, very good, impressive! He gave the appearance that his girls' correct homework made him profoundly happy, whereas he calmly and encouragingly reeled off perfect solutions if any of his students made a mistake, and held them out for his students to accept. Whereas all the women had arrived at the college believing that they were studying mathematics for their own futures, it was not long before there was the added bonus of studying mathematics because it made Stephen so happy. The only thing that really detracted from each year of his hard work was the sherry party he ran the day before the exam, where experience showed that refusing the sherry was the best way for students to score a first.

Salah Baoendi started out his mathematical journey in Tunisia and so in that sense he was a minority. He rose to fame in France working in partial differential equations, and then specialized in several complex variables and moved to California. In France Salah learned bureaucratic technique. He was a micromanager and if he was convinced of the benefits and moral righteousness of a course of action, then he could pull all the stops and call in favors from his extensive network across the academic community in order to win any case. Since very few highly successful research mathematicians wanted to spend much of their time on administration, Salah was quite effective behind many a closed door and became popular because he could always score for the profession if needed such as when he headed up the commission to restore Rochester's mathematics department after some ignorant administrators thought they could do better without it. Salah was a long player, and made executive decisions whenever he saw fit. For example he liked to be seen to support undervalued women by inviting them to visit his department when they were in the States. One time when there was a woman speaker in the analysis seminar, there was a question from a member of the audience and the speaker did not appear to know the answer so the person who asked the question rephrased it believing the speaker had not understood. Salah however intervened. "Let her go!" he commanded. He won another case, sparing the speaker humiliation of being seen to not understand their field, showing that Baoendi had departmental authority, and putting an end to an interruption that was wasting audience time. What he did not do however, was supply the answer to the fundamental question, which had been eclipsed, and forgotten by most.

If Arlie Petters is still alive and his demise was only virtual, then perhaps putting him up alongside all these other math greats is going to inspire him to post an update and new profile picture. The internet believes he is far away in Abu Dhabi.

https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/about/leadership-and-people/office-of-the-provost.html

Without wanting to embarrass Arlie, we want to talk a little bit about how his career derailed in the US. He was an assistant professor at Princeton University where he was welcomed to the mathematics department studying the fascinating subject of gravitational lensing. This is where two close images of a distant planet appear on powerful telescopes and it is believed that this is due to lensing of the light rays by dark matter. Obviously it is a very interesting phenomenon. Arlie was an important addition to the Princeton department from MIT, but he knew little about the US when he arrived, having focused on science. Arlie was blessed with an amazing wife from his home country who was even more proficient as a chef for large events than the other faculty wives. She was everything he wanted with an amazing body and mind. She was a graduate student who was set to have a solid career of her own. When he left Princeton to start his job at Duke, to celebrate leaving, he put on a big feast for the Princeton faculty where his wife and sister-in-law cooked the food, and Arlie went around modestly claiming to his enchanted colleagues that it was nothing. However, Arlie had struggled to find a social niche in the US. He had suffered from some racist comments up in Cambridge Massachusetts and decided to try to form a support group amongst the African American community when he arrived in Princeton. His efforts had however been thwarted by his own experiences of competition and elitism. There was a new African American undergraduate mathematics major at Princeton from the inner city who was one of a kind and touted as perhaps the top student in his year. Arlie reached out and formed a mentorship group for him which introduced him to other young black faculty across institutions. However, the student astonished everyone and dropped out of Princeton. It was rumored he felt socially isolated. Just beforehand Arlie had failed to support an African American graduate student who was struggling and did not bond with Arlie. Arlie described him as being ``dead wood" and he had dropped out of Princeton. Shortly after Arlie's wife amazed the faculty with her catering, Arlie and his wife unexpectedly split up. He had become obsessed with an American woman but he got together with a different one, and left his wife. His wife was soon picked up by a new American boyfriend forming a couple which took all the awards for couple's dancing on the Princeton party scene. Arlie seemed confused. He loved his new American girlfriend and his wife, but he got divorced. The last we heard from Arlie was an email he sent around to African American women from Duke apologizing for a newspaper article nobody had even seen where he had apparently been negative about women going into math.

Arlie was not the only mathematician whose marriage collapsed because he fell for someone else. We want to talk about Cora Sadosky because she was such a social benefit to mathematics being a warm, honest, friendly person who made other people believe they could easily do mathematics. Cora was originally from Argentina and represented the age of women's liberation. In particular, before women's liberation many countries specialized their women into housework at home, whilst many men used their relative freedom to also keep a mistress. It was even a problem in the upper classes. Cora was but one in a generation of women who wanted to have the types of freedoms and liberties which successful men were enjoying, and she did not separate her professional life from her passionate love affairs. She shared the details of one love affair with a junior mathematician, and there were rumors she had had a love affair with a senior mathematician but it broke up when he decided to stay with his wife. The victim of the affair was his daughter, a wonderful in fact amazing young woman who happened to look like the young Princess Margaret, but was jilted at the alter and never married. Nowadays we hear less about torrid love affairs.

Cora's legacy however has been almost obliterated in somebody's strange belief that scandal is contagious. Her graduate students have been moved to other advisors. Her record of influence stands empty. It was no doubt done with the best intentions whilst however representing a great big lie. There was no reason to fear Cora's students would go on to muddy their professional lives with the types of love affairs she was starting, or to imagine that she had tarnished them by virtue of supervising them. That would be paranoia. Each generation is different. Every culture unique. One of the things which educates the new generation is new data.

Completely changing the subject, Jeff Remmel was a mathematician in California who after being Chair of the mathematics department at UCSD, decided to become assistant dean. He was a competent dean, who looked out for the department. He had been a competent Chair, which means that he had not gotten into any major fights or started any. He was politically average. He did not particularly support the old. He did not particularly support the young. He did not particularly support women, and thought he could appeal to women by being charming, but found it wasn't quite enough. One of the administrative staff used to joke with him that he was a bit of a task master, but he kept his words securely focused on the job. Nobody knew that he had family problems until he died unexpectedly. Most people were very sad to hear the news because as bosses go he was relatively popular.

Dan Stroock was something of an enigma. He once described himself as having a dark and curly mind. Factually speaking that was probably true. Like most of the MIT faculty over fifty, Dan was fixated on getting elected to the National Academy of Sciences. What Dan most liked to do was spend time with untenured junior faculty and postdocs. He liked to have them around as a focus for his social conversation, and also his recreation activity which was playing squash. Some of Dan's other favorite things were the theater and midnight mass. He did not seem to like committee work and would let his young friends help him with his administrative duties such as hiring senior faculty. When it came to talking about his mathematical field, Dan was less of a leader. His main contribution was explaining how pathways should be developed onto manifolds a bit like unwinding a ball of string? Most likely he was trying to describe Brownian motion in path integration, but it was difficult to get him to find time in his conversation to elucidate. Dan was married to a wonderful wife who used to be a preschool teacher teaching young children to read. She would read the books again and again letting the children follow along until they could read the books themselves. Dan respected her, but argued bitterly with his oldest child, a son who did not want to go into academia. Dan had an enormous dog which he kept locked up for long periods in a small cage, because it would get frustrated and perhaps Dan did not really have the time to train it. It hardly made sense to have such a very big dog in the city. However, it might be expected with Dan coming from a family of lawyers. Dan was a little upset with his father who left most of his wealth to charity. His dad sometimes used to defend criminal cases, but apparently kept to his honor code and could not say someone was innocent if they told him otherwise and insisted on explaining to the court why they had committed the crime. This actually related to a famous historical court case in New York City where a tram operator had intentionally caused a major accident.

Steve Zucker died in 2019, and for legal reasons we need to remark that 2019 > 2015. Steve died without any wife or children. He had been in hospital in Baltimore, and had been on leave from work prior to that, and had been forced to take psychotropic drugs prior to that as a condition for teaching his class. It might have made sense for Steve to want to take drugs if they had made him happy and great at his job. However, as far as we know, the drug made Steve paranoid, irritable and in a state of constant anxiety. It is easy today to see Steve's impressive early mathematical contributions on the web and wonder how such a talented young man could end up in a tenure job where he would have signed a contract that would allow his employer to force him to take damaging drugs as a condition of employment. Was Steve determined to be a danger to himself or others? If so why was he teaching in a major university? If not, why did he not have help with perfecting his teaching? At the University of California San Diego for example, if one of their valuable faculty was struggling with issues in the classroom, they used to send over a young lady from the Office for Teaching Development to sit in his class and interact with his students and train that professor up to be able to say the right words and give enough explanations that the professor could score respectable numbers in those all important student evaluations.

Let's take another abrupt change of focus and remember Isadore Singer, who was a mathematician of significant fame, success and popularity. For a while he copied Raul Bott and spent a month or so in the winter visiting Mike Freedman at UCSD. He gave talks in mathematical physics for the department. He never really acclimatized to Southern California, which despite being a mild temperature in the winter, actually has most of its limited rainfall at that time. To people who live there year round, the rain is a very refreshing and magical experience. Singer however would grumble about not being able to get out and play tennis on those days. He might have been better off just a bit east in one of the popular desert resorts. His visits were however valuable and appreciated by the UCSD math faculty. Singer was a multitalented professional and was not afraid to devote his own spare time to networking politically. Being an MIT professor, he was apparently always welcome in the offices of elected representatives, and gave other mathematicians encouragement in engaging with their politicians. He said that he always went in with a twenty dollar bill as a token of his support for their work.

Walter Craig was a bundle of high energy. Being bilingual, he could carry on two conversations at the same time with two different people, one in English and one in French. He could also carry on two conversations at the same time with a single person, one about mathematics and the other one general gossip. He was sensitive about being a political unifier and it is reasonably likely that if you asked him what religion he was affiliated with he would reply "the same one as you". However, to spend a conference afternoon with Walter was not something to just stumble into. It required high energy levels to keep up with him whatever the task, talking or walking.

Thomas Branson was a mathematician teaching at the University of Iowa who worked in conformal geometry and its applications to mathematical physics. He worked primarily with the Danish mathematician Bent Orsted, and also with an African American mathematical physicist. Branson was apparently a workaholic, very serious about his field and earnest and serious in general, becoming a respected expert. He was also serious about long distance running and died early of a heart condition. Branson was married to a Nordic wife. He was a professional serious person who focused on mathematics and was not the gossipy type. It is a complete mystery why it is so difficult to find a photo of Thomas on the web. He was at the same time very ordinary looking and equally easy to recognize. He was tall with lean average build, pale skinned, with dark hair and a dark mustache and brown eyes and looked pretty typically European American.

Thomas

Branson?

Stephen Shatz was both a mathematician and a medical doctor decades before it became fashionable to research mathematical biology from the safety of the mathematics department. He was a very warm friendly person who had a large stock of interesting conversation from his unique dual professorship. It would have been impossible to guess that Stephen Shatz was divorced from a few hours of conversation. It just goes to show how successful marriage can even elude people who seem to be as about intelligent as it gets.

Ed Nelson was a friendly person although not outgoing. He was apparently a mathematical physicist. One good idea which Ed felt deserved more theoretical attention is the wok frying pan. He found the experimental results worthy of understanding.